5 months ago, I quit my tech job to move to Australia with my wife on a working holiday visa. We had just gotten married, had no dependents or financial obligations, and had always wanted to visit her mom here but couldn’t make it work. It was also a good opportunity to take the year to try something different and, hopefully, come back to real life with more energy.

I like riding bikes and wanted to look for jobs in bike shops. My skillset in this space is pretty limited, a fact I’m glad I didn’t realize at the time because I wouldn’t have had the confidence to walk into Venture Cycles in Noosa and ask for work. It turns out there is more to bicycles than applying chain lube once a month and knowing that there are two kinds of valves.

My job at Venture was a sales and customer service role, telling customers where they can find things in the shop and acting as a liason between them and the mechanics, who know everything and have limited time. Since I knew nothing, often this meant walking the customer over to the mechanics, at which point both the customer and I would learn something new.

I’ve learned a lot more about bikes, though it would take many more years of this for me to start feeling competent. I do have other skills, so I decided to put those to use making Bicyclopedia to try to organize a portion of the things I’ve learned here.

We’re wrapping up our Noosa stint at the end of the month and heading south to cooler climes. I’m also wrapping up my work on this project for the time being, though I’ll probably have to pick it back up when the mechanics point out everything I got wrong!

How it works

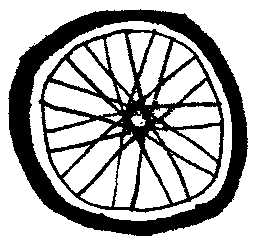

Each bicycle part was hand-drawn, photographed, and processed in GIMP so that it can be drawn on the canvas. I don’t have a tablet or any digital art skills (or analog art skills, for that matter) and I thought the amateur drawings were a good complement to my amateur bike skills. Processing the photos was straightforward: since they were just pencil on paper, you could take a photo, desaturate it, and apply a threshold filter to clamp the page to white and any pencil marks to black.

I wanted to show how the different parts fit together and got more complex as you pulled things apart. I decided to use HTML canvas to position and animate everything since it gave me the most control and also had a straightforward API for drawing images. Animating everything was a matter of defining a bunch of different states and assigning each part a position for each state. When animating between two states, I tracked progress with a number between 0 and 1 and used interpolation to average between the states depending on how far along the animation had progressed. If you raise the progress number to a power less than 1, you end up with an explosive effect at the start and an easing effect at the end. I thought this was the perfect complement to the Big Red Button™.

One thing about canvas is that once you draw something on the screen, it gets lost in the mass of pixels; you lose any reference to the original image. I needed a way to map pixels back to the parts they represented so that I could show labels and transition between states on click. You could probably make something proper that searches all parts to see if they were drawn in a given pixel, but doing intersections on an arbitrary, mostly-transparent PNG sounded much less fun than what I ended up doing instead: assigning each image two unique colours, one close to white and one close to black. That way, you just have to look up the RGB value of a pixel to know what was drawn there. As a bonus, it handles precedence automatically when there are multiple parts drawn on top of each other and it was easy to write a script to assign those colours with OpenCV.

Once I had animations and transitions, I had to write something about each part and show that on screen too. With canvas, you have to handle your own word wrapping. Since I was doing a bunch of text manipulation anyways, I thought it would be cool to make it look like the words were getting typed out letter by letter. It ended up being a fun diversion and I think it makes it bit easier to digest.

Toil can be good, actually

Writing the code for the states, animations, and text only took a couple days. Turning it into something interesting was far more time-consuming. There were over 100 hand-drawn icons that had to be cropped, processed, resized and positioned one by one. The end result was 1700 lines of Typescript, but only a few hundred related to the animations and state machines; the rest was just loading and positioning images. More importantly, I actually had to spend the time learning about each part. One benefit of cutting my income by a factor of 10 is that it’s not like I really had anything more valuable to do.

In the past, I’ve had a tendency to jump into the engineering challenges of a project and the details (information, presentation, etc.) has felt like a slog by comparison. This project, though, was all about the details. Getting them right involved a lot of work that I would previously have disregarded as toil, but seeing the finished product felt rewarding knowing the number of hours it took to put together. It’s also a lot easier to toil on something you care about.

Expertise

It’s been a really long time since I’ve been underqualified for a job. Starting at Venture was like going back to the first day of school again; I learned ten new things every day but left every day feeling like there were 100 more things I had become aware of but had yet to learn. I was surrounded by such an experienced group of mechanics and salespeople, and luckily they were patient enough with me not only to explain things to me, but to force me to learn by making me do things myself.

Even after I started feeling more comfortable with the basics, using them in practice was easier said than done; it’s one thing to know theoretically that there are different headset types but another thing entirely to have someone come in with a frame and a fork and ask you to fit them together. Everyone who comes into the shop usually does so with one question about one bike, but to be able to answer each customer requires you to have an almost unimaginable depth of knowledge. It was cool to see how much better I got at every aspect of the job in a short amount of time, but it was also humbling to realize how much further I had to go.

It got me thinking about how capable I am at the things I am qualified for. Software is a tricky space because although it helps, you don’t actually have to have an in-depth understanding of the systems you’re working with to get something usable out the door, now more so than ever. These days, we have so much at our fingertips that it’s easy to convince yourself that you know something better than you do. When everything is a quick search away, it feels like there isn’t the same pressure to remember it yourself. Before I quit my tech job, I had built up a modest amount of expertise in my field, but does it matter? Is expertise distinguishable from merely having that knowledge close at hand?

If you’re a bike mechanic, what I saw is that the answer is yes, overwhelmingly. It’s one thing to be able to Google how to change a tire and to do it yourself, but it’s another to have the expertise to know to check for punctures, to make sure the tire is beaded properly after inflating it, and to be able to re-attach it so that the chain is tensioned properly and so that the wheel stays on. These skills are even more important considering the consequences of being wrong are that someone gets seriously injured, and where a Google search can’t tell you if the job you’ve done is good or not. More relevant to my experience is that searching something in front of a customer doesn’t inspire a whole lot of confidence.

For software engineers, it’s more complicated. Your expertise matters, but not everything has to be internalized the same way because it’s a more forgiving environment; you can generally find an answer to most questions with a quick search. It’s not just an LLM thing: people have been copying and pasting StackOverflow snippets long before ChatGPT. But if answers are so easily accessible, is it still valuable to internalize that expertise so that you can get by without the help of tools? Can a lack of knowledge be made up for by the ability to have one’s questions answered as they come up?

I don’t know how things will shake out in the industry long-term, or even what the state of things will be when I come back to real life next year. If the answer to the questions above is yes, it takes a pretty dim view of the role of software engineers and how they can be useful. But I think there’s more to it than that; it’s one thing to have the knowledge readily available, but another thing entirely to be able to put it to good use. Personally, I have fun learning for its own sake, and I prefer to know things than to look them up; that’s why I play trivia. In-depth knowledge may come in handy down the line, or it won’t. But it feels much better to know things with confidence than to second-guess (or worse, fake it). Watching the bike mechanics for a few months solidified this for me.

This project was goofy in a lot of ways, but it was also a serious way to put that to the test. I obviously care about the end product, but how quickly I got there wasn’t as much of a factor to me as taking the time to build and understand it myself. And just like I’m glad I forced myself to learn more about bikes, I’m also glad I challenged myself to make something that was entirely my own.